The New River’s name is a misnomer, it is actually one of the oldest rivers in the world (although dating a river is difficult). The New may have been flowing north before parts of the Appalachian Mountains were pushed from the ground during the Alleghanian orogeny (mountain building event) roughly 320 years ago. As the mountains grew the river scoured and carved the rock away, forcing its way though solid rock.

The New River begins on the slopes of northwestern North Carolina then flows into VA and on into WV. There it joins the storied whitewater river known as the Gauley. Here the New and the Gauley form the Kanawha River which later joins the Ohio River near Point Pleasant, WV. Both the New and Gauley offer amazing whitewater boating.

In Virginia’s ridge and valley province, tributaries to the New River like Walker Creek, near Bland, TN flow between parallel ridges, meandering between lush farmland and remnant forest. Like many other rivers, cows and other livestock have direct access to the river are a contributor to non-point source pollution. When livestock have direct access to the river they muddy the water and erode the stream banks. They also add nutrients (especially nitrogen) and fecal bacteria directly into the water. Fecal bacteria (from human and livestock levels) in rivers is a public health problem worldwide (including the US).

I couldn’t find Podostemum in Walker Creek, despite the habitat looking pretty darn good for the plant.

Agriculture is currently exempt from the Clean Water Act of 1977 and a recent court ruling has put on hold regulations from 1977 to protect the many small streams that flow into large rivers, like the New and Gauley Rivers. It’s hard to have clean water in the river without clean water flowing into them.

Cows along the Clinch River, VA. The Clinch is a biologically diverse tributary to the Tennessee River.

After searching for Podostemum in several places in Walker Creek and coming up short, I finally found some growing at the confluence of Walker Creek and the New River. If Podostemum calls the New River home from North Carolina to West Virginia, why wouldn’t it be in this tributary?

Podostemum ceratophyllum at the confluence of the New River and Walker Branch. This Podostemum doesn’t look very happy to me. It looks quite red which might be a sign of stress in the plant.

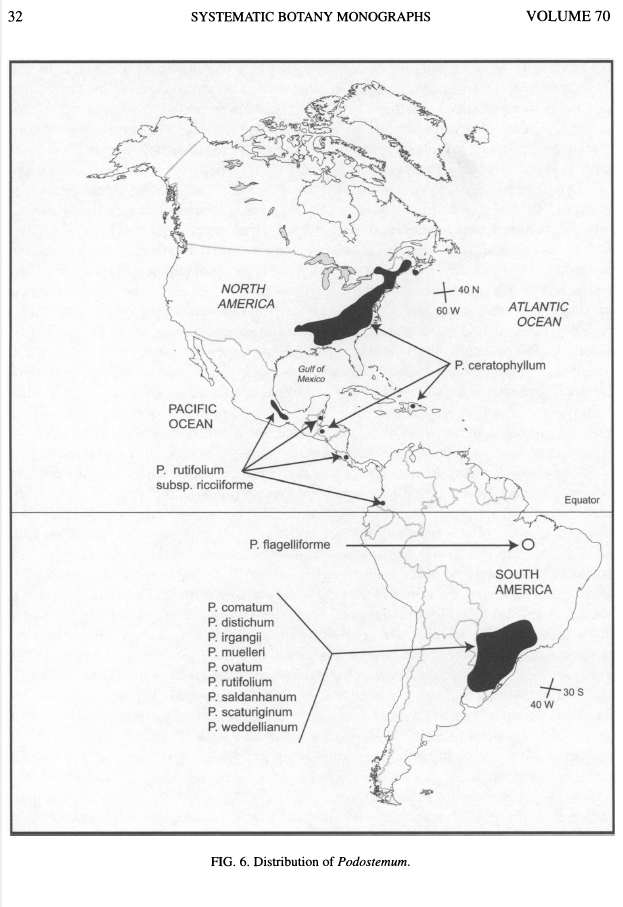

Maybe the plant hasn’t had a chance to get there yet, however Podostemum ceratophyllum seems to have been in the Southern Appalachians for a long long time. It was growing near the confluence of the New River and Walker creek, both on the upstream end and on the downstream side; and the plant grows over a large geographic area will little competition from other plants. Perhaps Podostemum isn’t there because of water pollution, but what type of water pollution could cause it to be absent from an entire river? How do I measure that type of pollution? Where is the pollution be coming from? Is it from coming from one source or many, and is the pollution always in the water or only sometimes, like when it’s raining? There are more questions than answers…

Please click the “Follow” tab and find out about new posts